Below are our key conclusions when considering rebalancing as part of an overall investment management:

- Developing asset allocation through a thoughtful understanding of the individual client remains the most important factor.

- Unemotional investment decisions are essential.

- Rebalances are essential for long-term asset management but are not the leading factor.

At the beginning of most of our relationships people rightfully ask “how do you manage our investments?” In response, we try to provide an in-depth discussion of our philosophies and our beliefs about best practices in portfolio management. While much consideration should be given regarding a client’s individual circumstances, the market/economy, proximity to needing funds, and economic trends, this article only focuses on rebalancing an account.

Rebalancing is the process of buying and selling assets in a portfolio periodically to maintain the original desired asset allocation. We believe that asset allocation is the most important decision in portfolio construction, and rebalancing is needed because of market volatility and allocation drift. Historically, stocks have outperformed bonds and therefore over time as the stocks continue to grow at a faster rate than bonds, the allocation to stocks increases. Holding all outside factors constant, this causes the general allocation of the portfolio to change if left alone. This change is referred to as allocation drift, and rebalancing seeks to address this general change in a portfolio’s makeup. When determining how often to rebalance, we must consider two underlying negative factors: trading costs and taxes.

Depending on the size of the account, trading costs can either be very significant or relatively immaterial. For example, in a $15,000 account, trading fees can have considerable impact on the overall account return. However, in an account of $1,500,000, the cost is a rounding error. We seek to eliminate or reduce trading fees on all accounts but pay particular attention to the smaller accounts.

The second underlying cost to rebalancing is taxes. The enormous benefit of tax preferenced accounts (IRAs, 401(k)’s, etc.) is that taxes are not due on sales of securities that result in gains. Instead, they are due when the distribution occurs. Alternatively, if a gain is taken in a taxable account, the investor pays tax on the gain for the calendar year of the transaction. While some capital gains are acceptable by investors, large unexpected gains can sometimes be an unwelcomed surprise come tax day. While we seek to invest the funds as close to our goals as possible, sometimes we will delay taking gains if we are close to our allocation or if the security is similar in nature to the position that we would be replacing it with. This is a very soft science calculation which does not always present a clear black and white answer.

Keeping trading fees and taxes in mind, we generally seek to only execute rebalances that have a material impact on the account. This can be accomplished by adding acceptable thresholds of how far out of “balance” an account can be before a rebalancing trade is identified. Said differently, when answering the “how often?” question, we generally want the account to be materially different from the ideal allocation before we will execute a rebalance. For example, let’s say that a market change caused an allocation to increase stocks by 6% and reduce bonds by 6%. Now a 60% equity and 40% bond portfolio became 66% equity and 34% bonds. This is not necessarily alarming but clearly a rebalance is in order sometime soon. Alternatively, let’s say that a market movement caused the portfolio to be 59.8% Equity and 40.2% bonds… does that require a rebalance? Not necessarily. We generally have an acceptable threshold around the allocation or the holdings to eliminate small trades that do not have material impacts on the long-term performance of the account.

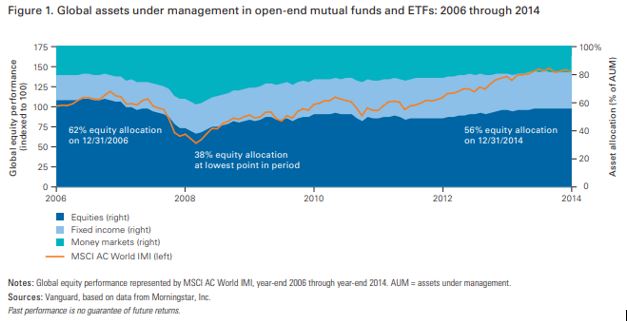

Rebalancing – not asset selection (the process of finding the best securities inside of the asset allocation) – should be methodical and unemotional. Statistics are continually published showing that the average investor does not stick with their goals during market volatility and makes the worst decision at the worst time. See the chart below from Vanguard, which demonstrates that investors move in and out of equities inversely to global market performance.

Source: https://www.vanguard.com/pdf/ISGPORE.pdf

Not surprising, Vanguard has spent a great deal of research to determine the most efficient strategy when it comes to rebalancing. In the above referenced article (Best Practices for Portfolio Rebalancing – November 2015), Vanguard makes the following conclusion:

Just as there is no universally optimal asset allocation, there is no universally optimal rebalancing strategy. The only clear advantage so far as maintaining a portfolio’s risk-and-return characteristics is that a rebalanced portfolio more closely aligns with the characteristics of the target asset allocation than with a never-rebalanced portfolio. As our analysis has shown, the risk-adjusted returns are not meaningfully different whether a portfolio is rebalanced monthly, quarterly, or annually; however, the number of rebalancing events and resulting costs increase significantly. As a result, we conclude that a rebalancing strategy based on reasonable monitoring frequencies (such as annual or semiannual) and reasonable allocation thresholds (variations of 5% or so) is likely to provide sufficient risk control relative to the target asset allocation for most portfolios with broadly diversified stock and bond holdings, without creating too many rebalancing events over the long term.

We seek to always stay abreast of the most relevant data available regarding investment management, which incorporates rebalancing. Vanguard’s research confirms our beliefs about how a portfolio should be rebalanced. Below are our key conclusions when considering rebalancing as part of an overall investment management:

- Developing asset allocation through a thoughtful understanding of the individual client remains the most important factor.

- Unemotional investment decisions are essential.

- Rebalances are essential for long-term asset management but are not the leading factor.